Exploring Learning Differently

Holistic Models

In addition to ongoing research about how valuable holistic approaches are for learning, current research, and innovative practice is beginning to show how particularly helpful they are for learning in the face of violence. To learn more about holistic learning and addressing impacts of violence on learning, read Why holistic literacy learning?

top of page

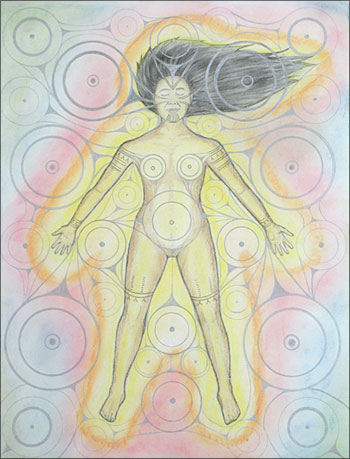

"Female Composition #1", Heather Campbell, 2008.

(pastel, coloured pencil and silver ink on paper. 18" x 24")

"In traditional Inuit spirituality, individuals are comprised of three different elements or "souls." Here I depict the souls as an aura, enveloping the woman in a warm and protective light. The woman's traditional facial and body tattoos have energy lines that connect with the universal energy called "sila" depicted by concentric circles. This image conveys protection and healing and illustrates the warmth, strength, and life giving spirit of women."

top of page

Nava's Model

While there are several models of holistic education, this one was developed by Ramon Gallegos Nava, a Mexican educator and director of the Foundation for Holistic Education. The model places spirit at the centre and the design shows how various dimensions of self are connected. The following descriptions are based on Nava’s work, writing by Virginia Griffith (2001) Leona English (2000), and Mary Norton (Norton, 2008).

The model includes six dimensions to think about as we find ways to support learning. Click on each word in the model for more about what it means:

Social: All learning happens in a social context of shared meaning (Nava, 2000). Holistic learning includes collaborative learning and authentic relationships (Griffinn, 2001; Tasmanian Holistic Education Network)

Emotional: Emotions accompany all learning and these emotions can affect the learning outcome (Nava, 2000). Emotions can be pleasant or difficult (e.g., joy and frustration) and different emotions can support or block learning.

Spiritual: Leona English (2002) describes spiritual as strong sense of who one is; care, concern and outreach to the other; and the continuous construction of meaning and knowledge. For Nava (2000), spiritual has to do with the “total and direct experience of universal love that establishes a sense of compassion, fraternity and peace towards all beings.” Griffin (2001, p. 121) describes spiritual as an awareness of all there is and an openness to what is not.

Mental: Nava (2000) describes the mental dimension in terms of thought processes and capacity to reason logically. (Nava, 2000). Griffith (2001) describes the mental dimension in terms of three related areas: rational/intellectual (left brain) metaphoric (right brain) and intuitive.

Physical: Nava (2000) and Griffith (2001) both acknowledge connections between mental and physical learning and knowing. Nava notes that all learning occurs in a physical body, and that mind-body harmony is important in learning (Nava, 2000). Griffith describes physical learning as including the five senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. The more senses are used in learning the more likely we are to understand and remember. Griffith also notes that our physical state can help or hinder learning. (Emotions are also connected to our physical state and can help or hinder learning.)

Aesthetic: Beauty as a key aspect of human existence.

References

English, L. (2000). Into the 21st century with spirit. New Horizons in Adult Education, 14 (1). Retrieved December 26, 2007

Griffith, V. R. (2001). Holistic learning/ teaching in adult education: Would you play a one-string guitar? pp. 105 – 130 in T. Barer-Stein and M. Kempf (Eds.), The craft of teaching adults. (3rd Ed.) Toronto: Irwin.

Nava, R. G. (2000). A multi-dimensional multi-level perspective of holistic education: An integrated mode. Holistic Education Network of Tasmania. Retrieved December 15, 2007

Norton, M. (2008). Invitation to the dance. A very small exploration of using arts-based approaches in adult literacy education. In E. Battell et al., Moving research about addressing impacts of violence on learning into practice. Edmonton, AB: Windsound Learning Society.

top of page

Medicine Wheels

It is important to note that there are various versions and teachings of the Medicine Wheel. The common elements are that each version represents four directions, four colours (usually red, yellow, black – or green or blue - and white) and teachings associated with those directions/colours. Each nation has its own teachings related to the Medicine Wheel.

Here are some links to some Medicine Wheel information on the internet:

Four Directions Teachings

This web-site was developed by InvertMedia Inc. and is a wealth of information from the perspective of various cultures. The team included First Nations and Métis people. The web-site provides free curriculum featuring Elders/traditional teachers:

- Stephen Augustine, Mi’kmaq;

- Reg Crowshoe and Geoff Crow Eagle, Pikani Blackfoot;

- Mary Lee, Cree;

- Lillian Pitawanakwat, Ojibwe; and,

- Tom Porter. Mohawk.

It provides audio narration for the teachings, accompanied by animated visuals as well as Teacher’s Resources links.

Mi’kmaw Spirituality

This web-site contains various teachings, including that of the Medicine Wheel. It has a chart showing the four directions, as well as the colour, guide, element, season and life stage associated with each. It has the following teaching on the author page: “Your talents are a gift from the Creator; how you use them is a gift you give back to the Creator.”

The Medicine Wheel – by Whiskeyjack, Francis

This web-site contains the Medicine Wheel teachings gathered by Whiskeyjack from Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Alberta. Whiskeyjack is careful to note that he is still learning. He incorporates the life stages, as well as the symbols and teachings associated with each direction.

Allying with the Medicine Wheel: Social Work Practice with Aboriginal People Verniest, Laura. (2007)

This article appears in Critical Social Work, 2006, Volume 7, No. 1. “This article uses a Medicine Wheel model, a structural social work framework and an anti-oppression stance, to practice culturally sensitive social work with Aboriginal peoples.” Verniest discusses the following: Stages of Being – Spiritual, Emotional, Physical and Mental; Client’s Location – Individual, Family, Community and Nation; Roles of a Social Worker – Counsellor, Educator, Facilitator and Advocator; and, Action Plan for Social Work Practice – Increased Healing, Increased Consciousness, Increased Organization and Increased Action.

Physical Activity and Healing Through the Medicine Wheel. Lavallee, Lynn F. (2007)

The author is Métis (Algonquin/Cree/French). Lavallee uses the Medicine Wheel as a framework to document how she was ‘involved in the research and developed or grew as a direct result’ in a martial arts program at the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto. Several themes related to historic trauma emerged through the sharing of the participants. Readers of this article will note similarities between the participants in the martial arts program and that of learners in Aboriginal adult literacy programs.

top of page

|